There is a distinct sinking feeling that comes with walking out to your yard in mid-July. You’ve mowed, you’ve watered, and you’ve invested time into your property. Yet, instead of a uniform carpet of green, you find expanding circles of straw-colored death or mysterious patches of slime.

For many homeowners, this is the moment “lawn burnout” sets in. You wonder if you applied the fertilizer wrong, if the dog ruined the grass, or if you should just pave the whole thing over.

Here is the reality: You are likely fighting biology, not your own incompetence.

Lawn diseases are not random acts of bad luck; they are biological events triggered by specific combinations of temperature, moisture, and fungal pathogens living in your soil’s thatch layer. To fix the problem—and stop it from returning next season—you need to move beyond “Why is my grass yellow?” and start thinking like a diagnostician.

This guide provides the clinical framework you need to distinguish between a simple mistake and a fungal infection, allowing you to treat the root cause rather than just fighting symptoms.

The 30-Second Diagnostic: Rule Out the “False Positives”

Before you rush to the store for fungicides, we must perform a “differential diagnosis.” Statistics show that a significant portion of “diseased” lawns are actually suffering from mechanical or chemical damage. Fungal pathogens have erratic, organic growth patterns. Man-made mistakes usually look geometric or sharp.

Use this framework to eliminate non-disease causes immediately.

The “Is It My Fault?” Filter

It is easy to blame a fungus, but often the culprit is a dull mower blade, a fertilizer spill, or a pet.

1. Fertilizer Burn vs. Disease

If you recently treated your lawn, look at the pattern. Did you stop the spreader to turn around? Did you overlap strips?

- The visual clue: Fertilizer burn often appears in straight lines, sharp angles, or distinct strips that match the width of your spreader. The grass turns straw-colored rapidly (within 48 hours) from the top down.

- The verdict: If the brown patch has sharp, straight edges, you likely need to learn what does fertilizer burn look like to confirm it wasn’t a pathogen.

2. Dog Urine vs. Disease

- The visual clue: Dog urine spots are circular, but they almost always feature a “fertilizer ring”—a bright, dark green perimeter of tall grass surrounding the dead center. This is caused by the high nitrogen content in the urine.

- The verdict: Fungal diseases rarely stimulate growth around the kill zone. If you see a bright green halo, it’s likely a pet issue.

3. Dull Mower Blades

- The visual clue: Look closely at the grass tip. Is it shredded and white/grey rather than cut clean?

- The verdict: Shredded tips lose moisture rapidly and turn the lawn a greyish-white cast, mimicking disease.

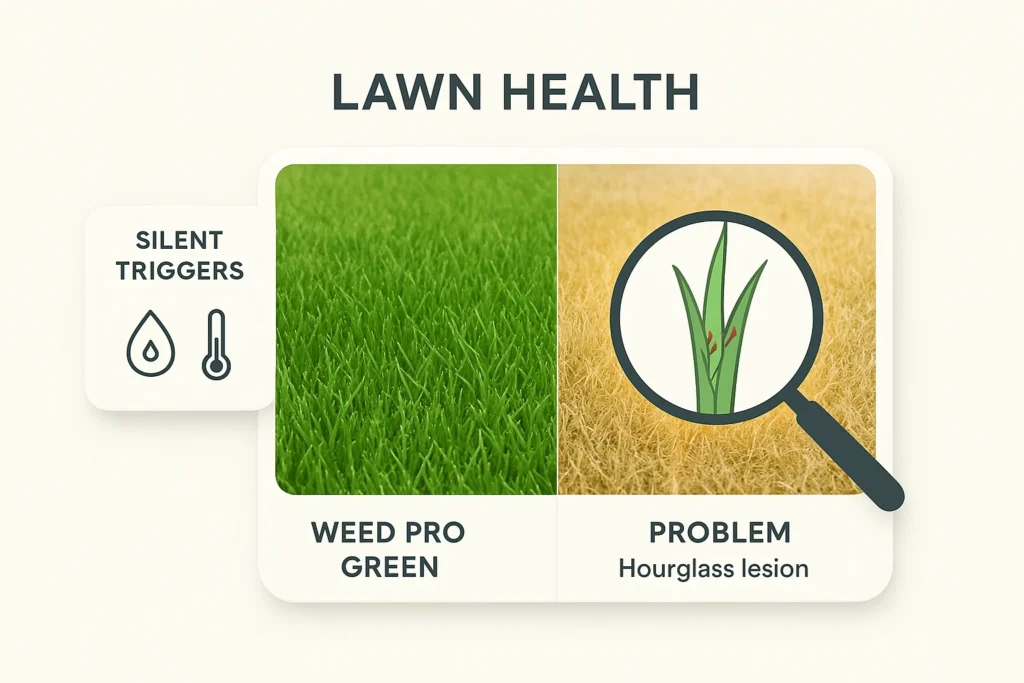

The “Silent Trigger”: The 12-Hour Rule

Once you have ruled out mechanical damage, you must understand why the disease is happening.

Fungal spores are always present in your lawn. They live in the thatch layer (the organic debris between the grass blades and the soil). However, they remain dormant until specific environmental triggers occur.

The most critical factor is Leaf Wetness Duration.

Research indicates that most major turf diseases require the grass blade to remain continuously wet for 10 to 12 hours to infect the plant. This is why a rainy afternoon doesn’t always cause disease, but a light dew that sits from 8:00 PM to 9:00 AM does.

- The Mechanism: When humidity is high and temperatures remain above 65°F (18°C) overnight, the moisture on the blade allows the fungal spores to germinate and penetrate the leaf tissue.

- The Takeaway: You cannot control the rain, but you can control your irrigation. Watering in the evening extends the “wetness window,” virtually guaranteeing infection in summer months.

Deep Dive: The “Big Four” Pathogens

If your lawn has passed the mechanical damage check and the weather has been humid, you are likely dealing with one of these four common offenders. Identification requires getting down on your hands and knees to examine the individual blades.

1. Brown Patch (Rhizoctonia solani)

This is the “humidity hunter.” It is prevalent in tall fescue and ryegrass, particularly during hot, muggy nights in Ohio and transitional zones.

- The Macroscopic View: You will see roughly circular patches ranging from a few inches to several feet in diameter. The grass inside the circle may look sunken or matted.

- The Microscopic Clue: Look at the perimeter of the patch early in the morning. You may see a dark, purplish-gray ring known as the “smoke ring.” On individual blades, look for irregular tan lesions with dark brown borders.

- The Trigger: High humidity and night temperatures above 68°F.

- Regional Note: While this is a major issue in the Midwest, it is also one of the frequent atlanta lawn problems due to the high heat and humidity in the South, proving that humidity management is universal.

2. Dollar Spot (Clarireedia jacksonii)

Dollar Spot often strikes when nitrogen levels are low and days are warm but nights are cool.

- The Macroscopic View: Small, silver-dollar-sized spots (2-6 inches) of bleached straw-colored grass. If left untreated, these spots can merge into large irregular blocks of dead turf.

- The Microscopic Clue: This has the most distinct “fingerprint.” Look for an hourglass-shaped lesion on the grass blade—bleached in the center with reddish-brown or purple margins at the top and bottom.

- The Webbing: On dewy mornings, you may see fine, white cobweb-like mycelium covering the spots.

3. Red Thread (Laetisaria fuciformis)

This disease looks alarming but is often less fatal than Brown Patch. It is a sign that your lawn is “hungry” (low nitrogen).

- The Macroscopic View: Irregular patches of ragged, pinkish-red grass. From a distance, the lawn looks like it has scorched, reddish areas.

- The Microscopic Clue: The key identifier is the presence of red, thread-like strands (stromata) extending from the tips of the grass blades. It looks like pink cotton candy has been pulled apart on your lawn.

4. Snow Mold (Gray and Pink)

Unlike the others, this is a cold-weather pathogen that incubates under snow cover.

- The Macroscopic View: As the snow melts, you find circular patches of matted, crusty grass. Gray Snow Mold causes white/gray patches; Pink Snow Mold has a distinct salmon-colored border.

- The Microscopic Clue: Hard, tiny sclerotia (resting bodies) may be found on the leaves—black for Gray Snow Mold, rusty-colored for Pink.

- Recovery: Raking these areas gently in spring to break the “crust” is one of the most essential seasonal yard tips to promote airflow and recovery.

The Lifecycle Solution: Why You Can’t Just “Spray and Pray”

Understanding the lifecycle changes how you treat the problem. Many homeowners apply fungicide after the damage is done and wonder why the grass remains brown.

The Reality of Sclerotia

Fungi like Rhizoctonia (Brown Patch) survive in the soil as sclerotia—hardened masses that can withstand extreme heat and cold for years. When you see a brown patch in turf, the fungus is already in its active feeding stage.

Fungicides stop the spread, but they do not “heal” the dead grass. The blade tissue is necrotic and must grow out. This is why proper diagnosis and timing are critical. If you spray too late, you are wasting money on a pathogen that has already gone dormant, while the damage remains visible until new growth appears.

The “I Hate Lawn Care” Prevention Plan

If the idea of tracking humidity and inspecting lesions sounds exhausting, you’re not alone. The good news is that 80% of disease prevention comes down to cultural habits, not chemical warfare.

You can disrupt the fungal lifecycle with three simple changes:

1. The Morning Water Rule

We cannot stress this enough: Never water in the evening. Watering between 4:00 AM and 8:00 AM allows the sun to dry the grass blades quickly, keeping the “leaf wetness duration” under that critical 10-hour threshold.

2. Manage the Thatch

Fungus lives in the thatch. If your lawn feels “spongy” when you walk on it, your thatch layer is likely too thick (over ½ inch), providing a perfect breeding ground for disease. Mechanical aeration and dethatching are the most effective ways to physically remove the pathogen’s habitat and improve drainage.

3. Raise Your Mower Deck

Cutting grass too short stresses the root system and reduces the plant’s ability to fight off infection. Higher grass also shades the soil, keeping roots cooler.

Conclusion: Partnering for a Healthier Lawn

Identifying lawn diseases is the first step toward reclaiming your yard, but it can be a complex process involving soil biology, weather patterns, and precise timing. You don’t have to become a plant pathologist to have a beautiful lawn—you just need to understand the basics and know when to call for backup.

Whether you are looking for an environmentally friendly treatment plan or a professional diagnosis to save a failing lawn, expert guidance can make the difference between a summer of frustration and a season of enjoyment.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: Can I just treat my lawn with fungicide every month to be safe?

A: We advise against blanket preventive spraying without a history of disease. Overuse of fungicides can lead to resistant strains of fungi and harm beneficial soil microorganisms. It is better to use Eco-friendly practices to build a resilient microbiome that fights disease naturally.

Q: Will the brown grass turn green again?

A: Dead tissue will not turn green. However, if the crown (the base of the plant) is alive, new green blades will eventually push out the dead ones. Recovery takes time—usually 2-3 weeks of active growth.

Q: How do I fix the bare spots left behind?

A: Once the disease is inactive, you can rake out the dead debris and overseed. However, ensure you are following proper lawn care tips for summer regarding watering, as new seedlings are delicate and disease-prone.